Forging

Forging is the process of shaping metal through the use of compressive force, causing plastic deformation of the piece, most often accomplished with the use of a hammer or die. Forgings may be hot or cold processed depending on the raw materials and the requirements of their application. Pieces can range in size and can be anywhere from a few grams to thousands of pounds; they may be created from a variety of metals or alloys. Items that are forged include kitchenware, tools, hardware, weapons, and jewelry. Engine blocks, ship's valves, and bits for mining are also examples of forged products. Specific jobs in the industry include boiler making, iron working, blacksmithing, and die cutting. There is a wide variety of work associated with the industry, such as casting, machining, and sheet metal fabrication. In larger operations, heavy equipment operators and drivers are necessary for the facilitation of production. Jobs in the field are predominantly held by men, with women making up a growing 5% of the industry.

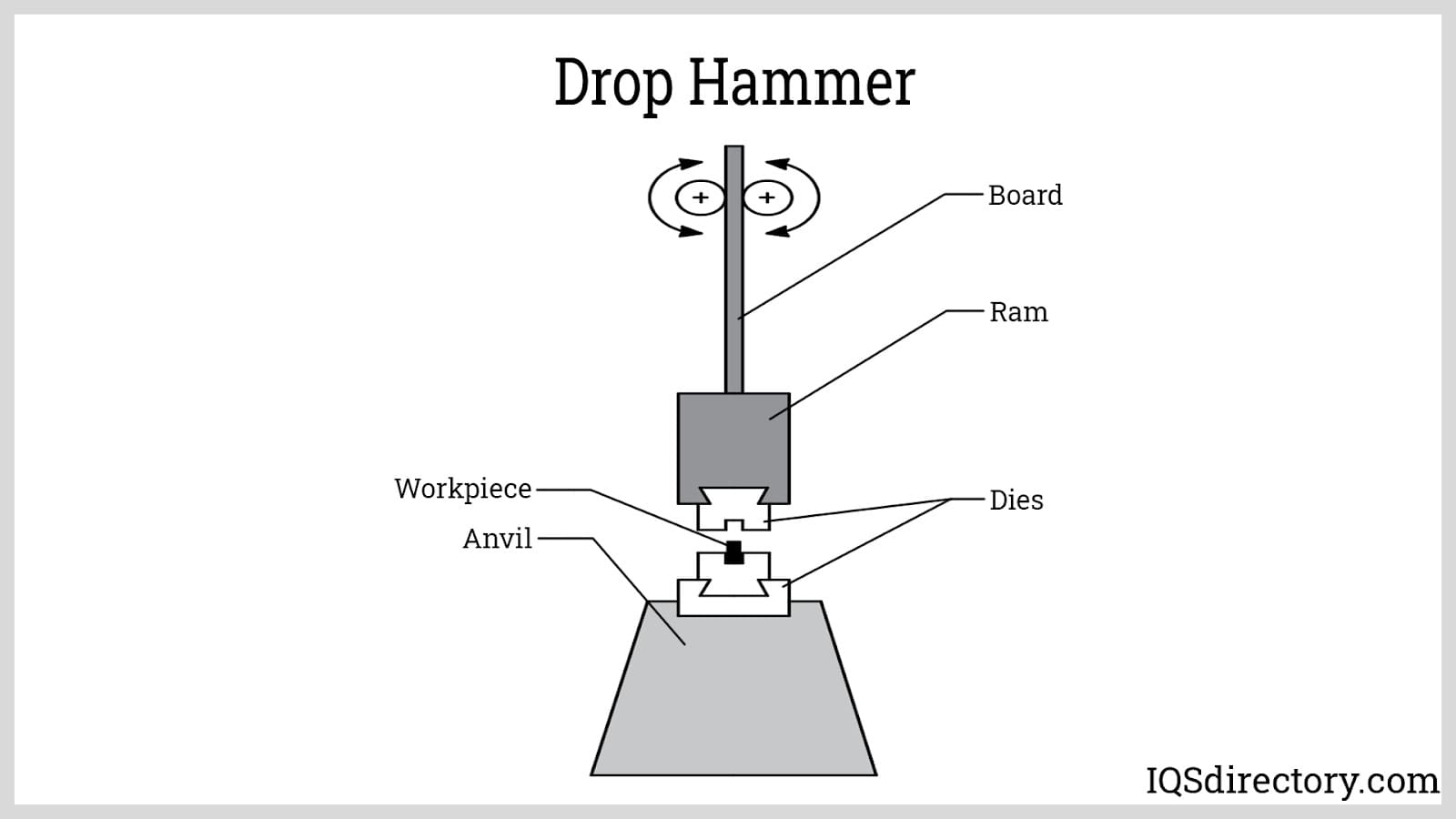

The Blacksmith's hammer and anvil were standard tools of the trade but are primitive in comparison to a hydraulic drop hammer, which can be built to accommodate most needs. There are forging presses that use high pressure to push metal into a mold or die. There are machines that hammer, roll, and bend metal into required shapes using pneumatics, hydraulics, or electricity. Forging is usually more cost effective than weld fabrication or casting, which requires the use of casting molds and molten metal. Forging requires few secondary operations, offers flexibility of design, and provides a strong product with few defects due to the lack of internal gas pockets.

Quick links to Forging Information

A Brief History of Forging

As early as 4500 B.C., Sumerians in the Tigris and Euphrates River Valleys were forging softer metals. They heated copper and bronze over fires and beat it with rocks to shape primitive tools. Around 750 B.C., during the Iron Age, the Bloomery Furnace, which was made of stone and clay and used bellows to create hotter fires, was invented. This allowed the utilization of iron. The ancient Romans prayed over their forges to the god Vulcan. During the 10th-12th centuries A.D., they invented the water wheel. These inventions, followed by the development of hammers and forced air bellows, increased productivity. There is evidence of metal horseshoes being forged as early as 900 A.D., but the primary products were knives and tools with some rudimentary jewelry developing on the eve of the Dark Ages.

During the Dark Ages, war was rampant in Europe. Weapons such as knives, swords, and spear heads were produced on a much larger scale. The industry flourished but did not change much until the Industrial Revolution. The 19th Century introduced the steam engine, which allowed power forges to be established virtually anywhere, creating opportunities for advancement around the world.

In 1856, the Bessemer Process was discovered. It was the mass production of steel made from pig iron using high temperatures and blasts of air, causing oxidation. With the abundance of resources, the Colt Arms Company developed the closed-die process and, with the aid of machining, was able to mass produce components for their guns. The modern forging press was designed in the 1930s. It applied constant pressure, rather than repetitive blows, to form metal.

Products of Forging and Their Applications

The forging process redirects the internal grain structure in metal, offering a stronger unit that may be reproduced ad infinitum or allow a poetic license to "sculpt" shapes in metal. Parts of any size may be created in a metal forge as the forge press may be built to any specification. New techniques offer higher degrees of integrity within the forging process, allowing for use of metals in increasingly technical ways. Forged parts are found in aerospace, aviation, defense, oil and gas, mining, shipping, transportation, and food processing industries in many forms, from the smallest bolt to ship anchors, train tracks, augers, and gears. You can find forged products such as bolts here on IQS Directory.

Materials Used in the Forging Process

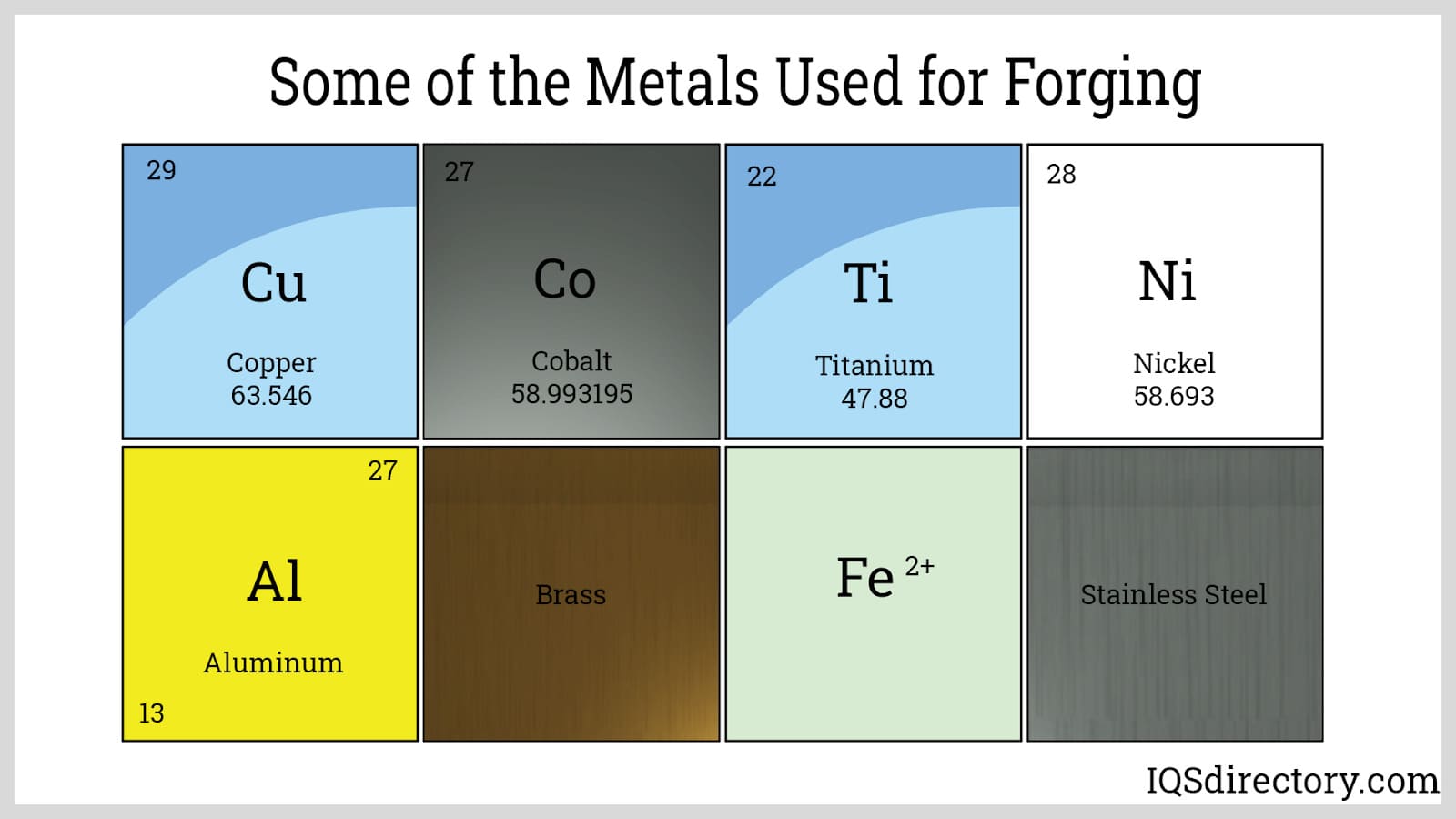

Metals commonly found in the forging process include iron, aluminum, titanium, copper, nickel, and alloys like brass, aluminum alloy, and stainless, carbon, or other alloy steel, as well as custom alloys for specific uses. Each metal has different properties and requires specific treatment. Heat forging raises the temperature of the metal above its recrystallization temperature, but not to its melting point, so that it can be formed by hammer or drop forge.

Iron has been the most used metal in forging for centuries due to its global abundance. Today, it is generally alloyed with other elements for strength and temperament. Aluminum has a low melting point, is lightweight, and has high tensile strength. Without aluminum, the aviation and aerospace industries could have never gotten off the ground. Copper is a soft, non-magnetic, non-sparking, yet electrically conductive metal. Nickel is resistant to oxidation and remains stable at elevated temperatures. Carbon Steel is lower in cost and can be heat treated (annealed) for further strength, and it provides good mechanical properties. Stainless steel is corrosion resistant. Titanium is costly, but is extremely strong and lightweight.

Forging Processes

Grain flow is the alignment of the crystalline structure within the metal. Base metals generally have a random orientation. The forging process alters the grain for a stronger, tougher, more ductile product that resists fatigue. The alteration of the grain flow is referred to as being drawn out or upset depending on the direction of the alignment. In a forging press, the crystalline structure is pushed from random alignment into a more ordered, multidirectional orientation, giving the piece its strength across multiple planes.

Typical processes include open die forge manufacturing, closed die forging, roll forging, swaging, cogging, upsetting, and automatic hot forging. These processes are performed at various temperatures and are classified by the relationship between temperature and recrystallization point. Hot forging happens when the temperature is higher than the recrystallization temperature of the metal. If the metal is below that point, but above 30% of the recrystallization temperature, it is considered warm forging. Cold forging occurs when the metal is cooler than its recrystallization point, often room temperature.

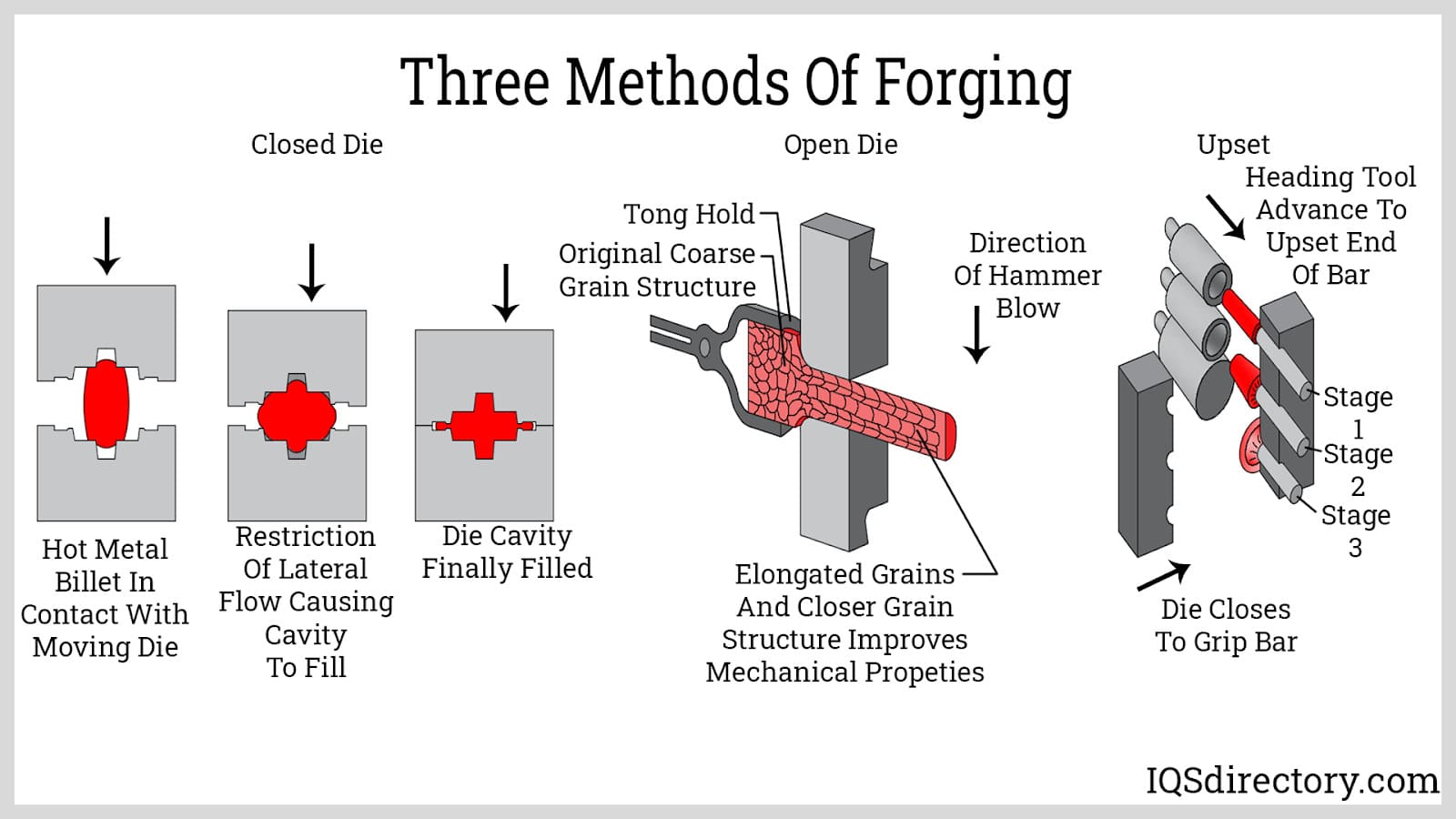

Open die forging, or smith forging, occurs when a workpiece is placed on a stationary anvil and deformed by forge hammer blows. The open dies do not enclose the workpiece, so it is allowed to flow except where in contact with the die. This process may be used to orient grain flow for increased strength, reduce the chance of voids, increase fatigue resistance, or improve microstructure. Cogging, edging, and fullering are techniques used in open die forging to bring the metal to the proper thickness, width, and concavity respectively. It is generally used for short runs, custom work, and artistic applications.

In closed-die forging, or impression-die forging, the metal is placed in a die, or mold, attached to an anvil. The hammer, which can also be shaped, is dropped on the workpiece, pressing the metal into the die's cavities. The excess metal, called "flash," is squeezed out of the sides of the cavity. The flash cools more quickly than the inner work piece, forming a sort of seal, which helps the metal fill the interior cavity more effectively, and it is removed after the piece is ready to be worked. The automatic hot forging process uses an automated forge machine. It starts with bars of metal heated almost instantly by the use of high-power induction coils. They are then descaled, cut into blanks, and formed through upsetting, preforming, final forging, and piercing. This process is typically used in high-speed manufacturing of smaller parts, such as nuts and washers.

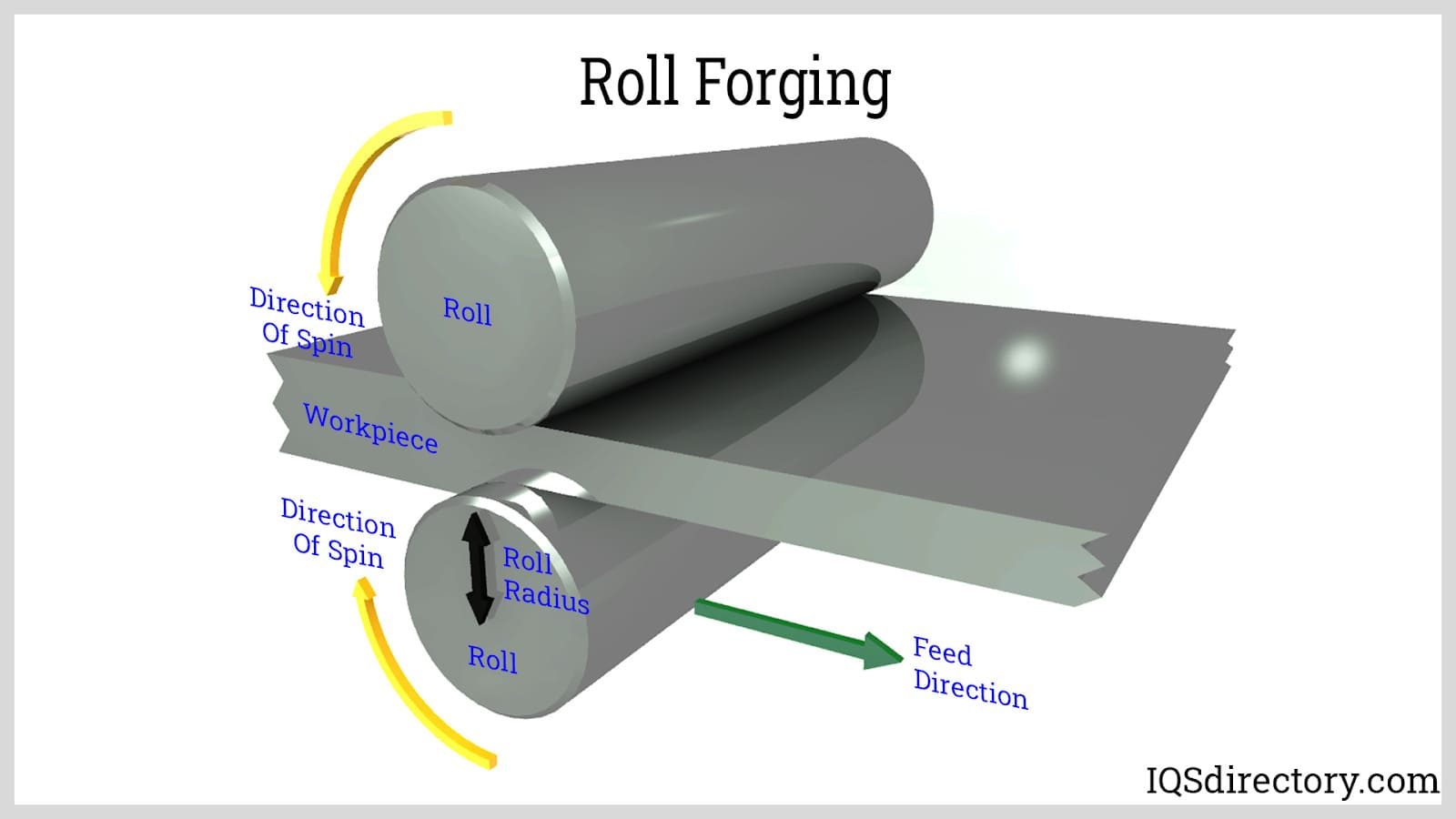

Roll forging is the passing of a heated bar between two grooved cylinders repeatedly until the material has achieved dimensional accuracy. This process imparts favorable grain structure into the metal and creates no flash, resulting in 20-30% less waste than closed-die forging. It is used for making items such as axles and leaf springs.

The advantages of the hot forging processes are the materials’ malleability due to higher temperatures, (resulting in less required force for deformation) and the constancy of tensile strength within the work piece. Hot forging of aluminum occurs at relatively low temperatures. 80% of forged aluminum is alloyed with silicon, magnesium, zinc, copper, and/or manganese to give it strength and stability.

Warm forging causes less scaling of the material's surface. It requires higher forming forces due to lower formability than hot forging, but formability is greater than in cold forging. Narrower tolerances may be achieved. Cold forging may be done at room temperature, allowing for ready handling of material. It offers the narrowest tolerances possible, absence of scaling of the surface finish, and increased strength. Cold forging is primarily used for processing softer metals, such as copper, brass, bronze, gold, silver, and platinum. You can find companies doing cold forging here on IQS Directory.

Forging Images, Diagrams and Visual Concepts

Different types of metal that can be forged.

Different types of metal that can be forged.

Roll forging is a heated metal process that uses opposing rolls to shape the material.

Roll forging is a heated metal process that uses opposing rolls to shape the material.

Power drop hammers use pressurized air to raise the ram to accelerate the dropping speed of the hammer.

Power drop hammers use pressurized air to raise the ram to accelerate the dropping speed of the hammer.

The three different methods of forging.

The three different methods of forging.

Forging Equipment

Different metals and different applications require the use of a variety of equipment. In the hot forge process and warm forge process, metal must be preheated prior to the forge work. This can be accomplished through the use of a torch, oven, or electrical induction. Ovens can be heated with coal or gas. Coal provides a hotter fire but requires constant tending. Gas is cleaner and more user friendly but more expensive. In the cold forging process, even a short stint in the sun may suffice for preheating.

A drop forge is a vertical hammer suspended over a stationary anvil. When the hammer drops, the workpiece on the anvil is deformed and the excess energy is absorbed by the foundation. You can find these types of forges here . A counter blow machine or impactor uses hydraulic, pneumatic, or electrical power to strike horizontally. The excess energy from the blow is absorbed as recoil. A forging press uses constant hydraulic or mechanical power to press the raw material into a die. A ring press forge uses heat and concentric forces to press stock into seamless rolled rings. A roll press forge is used by passing metal stock between cylinders repeatedly until dimensional accuracy is achieved.

Dies are manufactured for use in forging presses. They must be made from high-alloy steel or tool steel to withstand impact, temperature variance, and corrosion. They may be produced by mechanical milling or casting made from a prototype. In open die forging, the plates come in contact with the metal but are only required to stamp the image on its surface. In closed-die forging, the die plates must match each other's surfaces, allowing for a calculated percent of flash in order to meet specified dimensional tolerances. When casting molds, the prototype is placed in sand or covered in plaster to create a reverse image of the object. It is then removed from that mold and molten metal is poured into the void, forming a copy of the original. This copy is then used to create a more suitable mold out of alloy steel that will withstand the forging process and faithfully reproduce the original shape of the prototype.

Whether you’re an artist or manufacturer, it is important to find the right forge company to suit the needs of your project. A jewelry maker does not need a 20 ton press. A nut and bolt factory cannot survive on hand-hammered products. Whether you are working with precious metals, iron, or stainless steel will determine which forging process will work best. Many forge companies offer additional services. This may include heat treating, stress relieving, or hardening of stock, machining dies, or testing and analysis, such as radiography, ultrasonic testing, or dye penetrant testing. There are many good forge companies, but the right one will enhance every metal working experience. Whether it calls for a blacksmith to heat and beat some wrought iron tools or a machinist to create dies with precision contours, the right forge company is out there.

Forging Terms

- As Forged

- The condition of a forging as it comes out of the finisher cavity without any added operations.

- Backward Extrusion

- A process in which the metal flows in the opposing direction of the die and punch.

- Bar

- A metal piece that is hot rolled from a billet to form a round, hexagonal, square or rectangular shape.

- Bend

- Lengthwise deformation that occurs during forging or secondary operations, such as trimming.

- Billet

- A semi-finished, usually hot-rolled, uniform section metal product. Billets are relatively larger than bars for the most part.

- Block

- The forging operation in which metal is progressively formed to the desired shape and contour by means of an impression die.

- Bloom

- A semi-finished product of square or round cross section. This term is sometimes used interchangeably with "billet."

- Board Hammer

- A type of gravity drop hammer in which wood boards attached to the ram are raised vertically by action of contra-rotating rolls, then released. Forging energy is produced by the mass and velocity from the freely falling ram and the attached upper die.

- Cavity

- The recess in a die that gives shape to the forging. Cavities are typically created by machining.

- Coining

- A sizing process in which pressure is applied to forged parts to smooth part surfaces and fix deformations.

- Cold Working

- Changing properties, such as size, shape, and strength of an alloy, through plastic deformation of the metal at low to moderate temperatures below the recrystallization point of the metal.

- Die

- Part of press that punches shaped holes, cuts, or forms sheet metal.

- Discontinuities

- External and internal imperfections of a forging. External discontinuities include cracks, folds and laps; internal discontinuities include porous and segregated deformations.

- Drifting

- The formation of a hole or the enlargement of an existing hole in a forging through punching.

- Efficiency

- The amount of applied energy that is utilized in the deforming of the workpiece, expressed as a percentage of the total energy expended by the forging equipment.

- Extrusion

- The process of forcing metal to flow through a die opening in the same direction in which energy is being applied. Extrusion is used in many die-forging applications.

- Flash

- Excess metal that extends past the parting line of the die set, blocking metal from flowing past the die lines and filling the die impressions.

- Flow Stress

- The measurement of the deformation resistance of a substance dependent on factors such as temperature.

- Forging rings

- Modern forged rings have many uses, such as parts for machine tools, aerospace applications, turbines, and pipe and pressure systems. These rings are usually forged with stainless steel, tool steel, aluminum, copper, steel alloy, or the like.

- Large forging

- The process of forging has evolved over many centuries to the point that humans are capable of producing very large forgings. This capability and the large forgings it creates are now an integral part of modern infrastructure and everyday life.

- Ram

- The mechanism on a press to which the punch is fastened and that forces the punch through the die.

- Ring forging

- Ring forging is the process of manipulating metal into a hollow, circular or cylindrical “ring” shape by applying localized, compressive force.

- Trimming

- Secondary operation in which a forging is cut down to desired shape and size by removing flash from the forging.

- Twist

- Forging deformation that occurs along the width of the forging.